5.1 Linear conjugate gradient method

In this section, we will consider the following square system of n n n

Q x = p , Q ≻ 0 Q x = p, \quad Q \succ 0 Q x = p , Q ≻ 0 where x ∈ R n x \in \mathbb{R}^n x ∈ R n Q ∈ R n × n Q \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n} Q ∈ R n × n p ∈ R n p\in \mathbb{R}^n p ∈ R n

First, we recall that (1)

We already encountered systems of the form (1) least squares problems .

Consider the least squares problem

minimize ∥ y − A x ∥ 2 2 subject to x ∈ R n A ∈ R m × n , y ∈ R m \begin{array}{ll}

\minimize& \Vert y - A x\Vert_2^2\\

\st & x \in \mathbb{R}^n

\end{array}\quad \quad A \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}, y \in \mathbb{R}^m minimize subject to ∥ y − A x ∥ 2 2 x ∈ R n A ∈ R m × n , y ∈ R m where we assume that rank A = n \rank{A} = n rank A = n normal equations for this optimization problem are

∇ f ( x ) = 0 ⇔ A ⊤ A x = A ⊤ y \nabla f(x) = 0 \Leftrightarrow A^\top A x = A^\top y ∇ f ( x ) = 0 ⇔ A ⊤ A x = A ⊤ y Now, pose Q = A ⊤ A Q = A^\top A Q = A ⊤ A p = A ⊤ y p = A^\top y p = A ⊤ y (1) Q ≻ 0 Q \succ 0 Q ≻ 0 rank A = n \rank A = n rank A = n

Preliminaries ¶ Conjugacy property ¶ Conjugate gradient methods rely on the conjugacy property.

Let Q ∈ R n × n Q \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n} Q ∈ R n × n { d 0 , d 1 , … , d ℓ } \lbrace d_0, d_1, \ldots, d_\ell\rbrace { d 0 , d 1 , … , d ℓ } conjugate with respect to Q Q Q

d i ⊤ Q d j = 0 for all i ≠ j . d_i^\top Qd_j = 0\text{ for all } i\neq j. d i ⊤ Q d j = 0 for all i = j . Note that if d 1 , … , d ℓ d_1, \ldots, d_\ell d 1 , … , d ℓ Q Q Q

This property motivates a first algorithm, known as the conjugate direction method.

Conjugate directions method ¶ Let x ( 0 ) ∈ R n x^{(0)} \in \mathbb{R}^n x ( 0 ) ∈ R n { d 0 , d 1 , … , d ℓ } \lbrace d_0, d_1, \ldots, d_\ell\rbrace { d 0 , d 1 , … , d ℓ }

At iteration k k k

x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k x^{(k+1)} = x^{(k)}+\alpha_k d_k x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k where α k \alpha_k α k optimal step size for the quadratic function associated to the systems of equations Q x = p Qx = p Q x = p

Computation of the optimal stepsize α k \alpha_k α k

Let ϕ ( α ) = 1 2 t ( α ) ⊤ Q t ( α ) − p ⊤ t ( α ) \phi(\alpha) = \frac{1}{2} t(\alpha)^\top Qt(\alpha) - p^\top t(\alpha) ϕ ( α ) = 2 1 t ( α ) ⊤ Qt ( α ) − p ⊤ t ( α ) t ( α ) = x ( k ) + α d k t(\alpha) = x^{(k)}+\alpha d_k t ( α ) = x ( k ) + α d k α k = arg min α ϕ ( α ) \alpha_k = \argmin_{\alpha} \phi(\alpha) α k = arg min α ϕ ( α )

It is a quadratic convex function of α \alpha α α k \alpha_k α k

ϕ ′ ( α ) = d k ⊤ Q [ x ( k ) + α d k ] − p ⊤ d k = α d k ⊤ Q d k + d k ⊤ [ Q x ( k ) − p ] \begin{align*}

\phi'(\alpha) &= d_k^\top Q\left[x^{(k)}+\alpha d_k\right] - p^\top d_k\\

&= \alpha d_k^\top Qd_k + d_k^\top\left[Qx^{(k)}-p\right]

\end{align*} ϕ ′ ( α ) = d k ⊤ Q [ x ( k ) + α d k ] − p ⊤ d k = α d k ⊤ Q d k + d k ⊤ [ Q x ( k ) − p ] Define r k = Q x ( k ) − p r_k = Qx^{(k)}-p r k = Q x ( k ) − p k k k

α k = − d k ⊤ r k d k ⊤ Q d k \alpha_k = -\frac{{d_k^\top r_k}}{d_k^\top Qd_k} α k = − d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ r k The sequence { x ( k + 1 ) } \lbrace x^{(k+1)}\rbrace { x ( k + 1 ) }

x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k , where α k = − d k ⊤ r k d k ⊤ Q d k x^{(k+1)} = x^{(k)}+\alpha_k d_k, \text{ where } \alpha_k = -\frac{{d_k^\top r_k}}{d_k^\top Qd_k} x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k , where α k = − d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ r k where the { d k } \lbrace d_k\rbrace { d k } x ⋆ x^\star x ⋆ (1) n n n

Proof

Let us consider n n n R n \mathbb{R}^n R n σ 0 , … , σ N − 1 ∈ R \sigma_0, \ldots, \sigma_{N-1} \in \mathbb{R} σ 0 , … , σ N − 1 ∈ R

x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) = ∑ i = 0 n − 1 σ i d i . x^\star - x^{(0)} = \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \sigma_i d_i. x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) = i = 0 ∑ n − 1 σ i d i . By using the conjugacy property, we can obtain the value of σ k \sigma_k σ k

d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) ] = d k ⊤ Q [ ∑ i = 0 n − 1 σ i d i ] = σ k d k ⊤ Q d k \begin{align*}

d_k^\top Q\left[x^\star - x^{(0)}\right] &= d_k^\top Q\left[\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \sigma_i d_i\right]= \sigma_k d_k^\top Qd_k

\end{align*} d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) ] = d k ⊤ Q [ i = 0 ∑ n − 1 σ i d i ] = σ k d k ⊤ Q d k hence σ k = d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) ] d k ⊤ Q d k \sigma_k = \frac{ d_k^\top Q\left[x^\star - x^{(0)}\right]}{d_k^\top Qd_k} σ k = d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) ] α k = σ k \alpha_k = \sigma_k α k = σ k

By the recursion formula, we have for k > 0 , x ( k ) = x ( 0 ) + ∑ i = 0 k − 1 α i d i k>0, x^{(k)} = x^{(0)} + \sum_{i=0}^{k-1}\alpha_i d_i k > 0 , x ( k ) = x ( 0 ) + ∑ i = 0 k − 1 α i d i

d k ⊤ Q x ( k ) = d k ⊤ Q x ( 0 ) ⇔ d k ⊤ Q [ x ( k ) − x ( 0 ) ] = 0 \begin{align*}

d_k^\top Q x^{(k)} &= d_k^\top Q x^{(0)} \Leftrightarrow d_k^\top Q\left[ x^{(k)} - x^{(0)}\right] = 0

\end{align*} d k ⊤ Q x ( k ) = d k ⊤ Q x ( 0 ) ⇔ d k ⊤ Q [ x ( k ) − x ( 0 ) ] = 0 and as a result

d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) ] = d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( k ) ] = d k ⊤ [ p − Q x ( k ) ] = − d k ⊤ r k d_k^\top Q\left[x^\star - x^{(0)}\right] = d_k^\top Q\left[x^\star - x^{(k)}\right] = d_k^\top \left[p - Qx^{(k)}\right] = - d_k^\top r_k d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( 0 ) ] = d k ⊤ Q [ x ⋆ − x ( k ) ] = d k ⊤ [ p − Q x ( k ) ] = − d k ⊤ r k which permits to conclude that α k = σ k \alpha_k = \sigma_k α k = σ k

In addition, we have the following additional properties.

Proofs can be found in Nocedal & Wright (2006, p. 106)

The linear conjugate gradient (CG) method ¶ The conjugate directions method of Algorithm 1 { d k } \lbrace d_k\rbrace { d k }

the eigenvalue decomposition of Q Q Q

a modification of the Gram-Schmidt process to produce a set of conjugate directions.

This is, however, too costly for large scale applications.

directions d k d_k d k

each new direction d k d_k d k d k − 1 d_{k-1} d k − 1 d 0 , d 1 , … , d k − 1 d_{0},d_{1}, \ldots, d_{k-1} d 0 , d 1 , … , d k − 1

cheap computational cost and memory storage.

Main idea and preliminary CG version ¶ Choose the direction d k d_k d k − r k -r_k − r k d k − 1 d_{k-1} d k − 1

d k = − r k + β k d k − 1 d_k = -r_k + \beta_k d_{k-1} d k = − r k + β k d k − 1 where β k \beta_k β k d k d_k d k d k − 1 d_{k-1} d k − 1

d k − 1 ⊤ Q d k = 0 ⇒ β k = d k − 1 ⊤ Q r k d k − 1 ⊤ Q d k − 1 d_{k-1}^\top Q d_k = 0 \Rightarrow \beta_k = \frac{d_{k-1}^\top Qr_{k}}{d_{k-1}^\top Qd_{k-1}} d k − 1 ⊤ Q d k = 0 ⇒ β k = d k − 1 ⊤ Q d k − 1 d k − 1 ⊤ Q r k This gives us a preliminary version of CG.

Starting from x ( 0 ) ∈ R n x^{(0)}\in \mathbb{R}^n x ( 0 ) ∈ R n d 0 = − r 0 d_0 = - r_0 d 0 = − r 0

x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k , where α k = − d k ⊤ r k d k ⊤ Q d k d k + 1 = − r k + 1 + β k + 1 d k , where β k + 1 = d k ⊤ Q r k + 1 d k ⊤ Q d k \begin{align*}

x^{(k+1)} &= x^{(k)}+\alpha_k d_k, \text{ where } \alpha_k = -\frac{{d_k^\top r_k}}{d_k^\top Qd_k}\\

d_{k+1} &= -r_{k+1}+\beta_{k+1} d_k, \text{ where } \beta_{k+1} = \frac{d_{k}^\top Qr_{k+1}}{d_{k}^\top Qd_{k}}

\end{align*} x ( k + 1 ) d k + 1 = x ( k ) + α k d k , where α k = − d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ r k = − r k + 1 + β k + 1 d k , where β k + 1 = d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ Q r k + 1 This first version is practical for studying properties of CG. To do this, we need to introduce the notion of Krylov subspace , which is very useful in numerical linear algebra..

Given a matrix Q Q Q n × n n\times n n × n r r r n n n k k k r r r K ( r ; k ) = Span { r , Q r , Q 2 r , … , Q k r } \mathcal{K}(r; k) = \operatorname{Span}\lbrace r, Qr, Q^2 r, \ldots, Q^k r \rbrace K ( r ; k ) = Span { r , Q r , Q 2 r , … , Q k r }

Proof

See Nocedal & Wright (2006, pp. 109-111)

Here are some important takeaways from the theorem:

residuals { r k } \lbrace r_k\rbrace { r k }

Residuals r k r_k r k d k d_k d k k k k r 0 r_0 r 0

the search directions d 0 , d 1 , … , d N − 1 d_0, d_1, \ldots, d_{N-1} d 0 , d 1 , … , d N − 1 Q Q Q

by the conjugate direction theorem n n n

these results all depend on the choice of d 0 d_0 d 0 d 0 ≠ − r 0 d_0 \neq - r_0 d 0 = − r 0 x ( 0 ) x^{(0)} x ( 0 )

Practical CG algorithm ¶ Using Property 1 Theorem 2 improve the computations of α k \alpha_k α k β k + 1 \beta_{k+1} β k + 1 :

α k = − d k ⊤ r k d k ⊤ Q d k = − [ − r k + β k d k − 1 ] ⊤ r k d k ⊤ Q d k = ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 d k ⊤ Q d k \begin{align*}

\alpha_k = -\frac{d_k^\top r_k}{{d_k^\top Qd_k}} &= -\frac{\left[-r_k + \beta_kd_{k-1}\right]^\top r_k}{d_k^\top Qd_k} = \frac{\Vert r_k\Vert_2^2}{{d_k^\top Qd_k}}

\end{align*} α k = − d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ r k = − d k ⊤ Q d k [ − r k + β k d k − 1 ] ⊤ r k = d k ⊤ Q d k ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 Moreover, observe that r k + 1 − r k = α k Q d k r_{k+1}-r_k = \alpha_k Qd_k r k + 1 − r k = α k Q d k

β k + 1 = d k ⊤ Q r k + 1 d k ⊤ Q d k = d k ⊤ Q d k ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 [ r k + 1 − r k ] ⊤ r k + 1 d k ⊤ Q d k = ∥ r k + 1 ∥ 2 2 ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 \beta_{k+1} = \frac{d_{k}^\top Qr_{k+1}}{d_{k}^\top Qd_{k}} = \frac{{d_k^\top Qd_k}}{\Vert r_k\Vert_2^2} \frac{\left[r_{k+1}-r_k\right]^\top r_{k+1}}{d_k^\top Qd_k} = \frac{\Vert r_{k+1}\Vert_2^2}{\Vert r_{k}\Vert_2^2} β k + 1 = d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ Q r k + 1 = ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 d k ⊤ Q d k d k ⊤ Q d k [ r k + 1 − r k ] ⊤ r k + 1 = ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 ∥ r k + 1 ∥ 2 2 where we used the orthogonality of residuals.

This leads to the following practical algorithm.

Input: x ( 0 ) x^{(0)} x ( 0 )

Set r 0 = Q x ( 0 ) − p r_0 = Qx^{(0)} - p r 0 = Q x ( 0 ) − p d 0 = − r 0 d_0 = -r_0 d 0 = − r 0

Set k = 0 k = 0 k = 0

While ∥ r k ∥ 2 ≠ 0 \|r_k\|_2 \neq 0 ∥ r k ∥ 2 = 0 do :

α k = ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 / ( d k ⊤ Q d k ) \alpha_k = \|r_k\|_2^2 / (d_k^\top Q d_k) α k = ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 / ( d k ⊤ Q d k )

x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k x^{(k+1)} = x^{(k)} + \alpha_k d_k x ( k + 1 ) = x ( k ) + α k d k

β k + 1 = ∥ r k + 1 ∥ 2 2 / ∥ r k ∥ 2 2 \beta_{k+1} = \|r_{k+1}\|_2^2 / \|r_k\|_2^2 β k + 1 = ∥ r k + 1 ∥ 2 2 /∥ r k ∥ 2 2

d k + 1 = − r k + 1 + β k + 1 d k d_{k+1} = -r_{k+1} + \beta_{k+1} d_k d k + 1 = − r k + 1 + β k + 1 d k

k = k + 1 k = k+1 k = k + 1

Return x ( k ) x^{(k)} x ( k )

Numerical illustration ¶ Theorem 2 x ⋆ x^\star x ⋆ n n n

Solve system Q x = p Qx = p Q x = p Q = λ I n , λ > 0 Q=\lambda {I}_n, \lambda > 0 Q = λ I n , λ > 0

First residual r 0 = λ x ( 0 ) − p r_0 = \lambda x^{(0)} - p r 0 = λ x ( 0 ) − p d 0 = − r 0 d_0 = -r_0 d 0 = − r 0

x ( 1 ) = x ( 0 ) − ∥ λ x ( 0 ) − p ∥ 2 λ ∥ λ x ( 0 ) − p ∥ 2 ( λ x ( 0 ) − p ) = x ( 0 ) − x ( 0 ) + λ − 1 p = x ⋆ x^{(1)} = x^{(0)} - \frac{\Vert \lambda x^{(0)} - p\Vert^2}{\lambda \Vert \lambda x^{(0)} - p\Vert^2} (\lambda x^{(0)} - p) = x^{(0)} - x^{(0)} + \lambda^{-1}p = x^\star x ( 1 ) = x ( 0 ) − λ ∥ λ x ( 0 ) − p ∥ 2 ∥ λ x ( 0 ) − p ∥ 2 ( λ x ( 0 ) − p ) = x ( 0 ) − x ( 0 ) + λ − 1 p = x ⋆ Then r k + 1 = 0 r_{k+1} = 0 r k + 1 = 0 d k + 1 = 0 d_{k+1} = 0 d k + 1 = 0 x ( 0 ) x^{(0)} x ( 0 )

In fact,

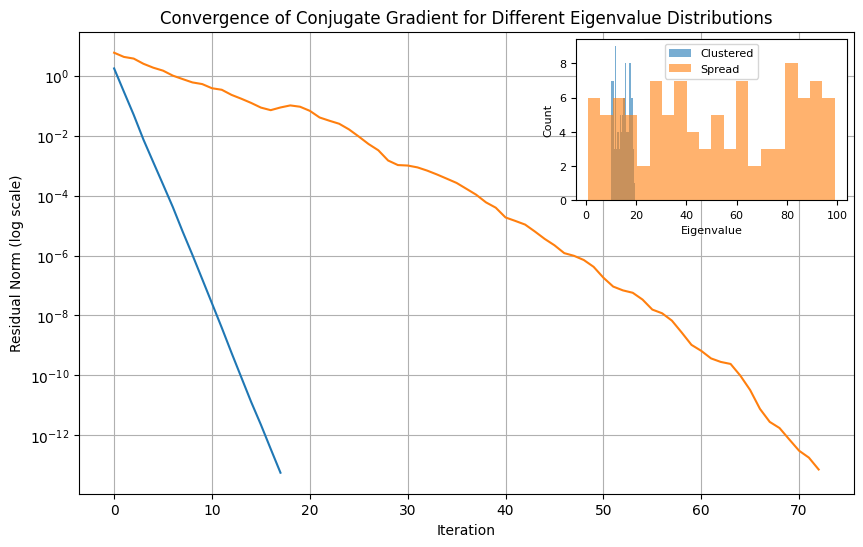

convergence of CG usually depends on the \alert{distribution of eigenvalues of Q Q Q

it can be shown that if Q Q Q r r r r r r

The following example shows how CG convergence speed can be affected by the distrubution of eigenvalues.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.sparse.linalg import cg

from mpl_toolkits.axes_grid1.inset_locator import inset_axes

# Function to run CG on a system with matrix A and show convergence rates

def run_cg(A, b):

x0 = np.zeros_like(b)

residuals = []

# Custom callback function to record residuals at each iteration

def callback(xk):

residuals.append(np.linalg.norm(b - A @ xk))

# Run CG algorithm

x, _ = cg(A, b, x0=x0, rtol=1e-14, callback=callback, maxiter=x0.size)

return residuals

# Problem setup

n = 100

np.random.seed(10)

b = np.random.randn(n)

# Case 1: Well-clustered eigenvalues

eigenvalues_clustered = 10 + 10 * np.random.rand(n)

A_clustered = np.diag(eigenvalues_clustered)

residuals_clustered = run_cg(A_clustered, b)

# Case 2: Spread-out eigenvalues

eigenvalues_spread = 100 * np.random.rand(n)

A_spread = np.diag(eigenvalues_spread)

residuals_spread = run_cg(A_spread, b)

# Plot convergence rates

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.semilogy(residuals_clustered, label="Clustered Eigenvalues")

ax.semilogy(residuals_spread, label="Spread Eigenvalues")

ax.set_xlabel("Iteration")

ax.set_ylabel("Residual Norm (log scale)")

ax.set_title("Convergence of Conjugate Gradient for Different Eigenvalue Distributions")

ax.grid(True)

ax.legend()

# Add inset for eigenvalue distributions

axins = inset_axes(ax, width="35%", height="35%", loc='upper right')

axins.hist(eigenvalues_clustered, bins=20, alpha=0.6, label="Clustered")

axins.hist(eigenvalues_spread, bins=20, alpha=0.6, label="Spread")

#axins.set_title("Eigenvalue Distribution", fontsize=10)

axins.set_xlabel("Eigenvalue", fontsize=8)

axins.set_ylabel("Count", fontsize=8)

axins.tick_params(axis='both', which='major', labelsize=8)

axins.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.show()Summary ¶ For which problems?

Solve “square” linear systems of the form Q x = p Qx = p Q x = p Q ≻ 0 Q \succ 0 Q ≻ 0

For strictly convex quadratic problems with objective 1 2 x ⊤ Q x − p ⊤ x , Q ≻ 0 \frac{1}{2}x^\top Qx - p^\top x, Q \succ 0 2 1 x ⊤ Q x − p ⊤ x , Q ≻ 0

Key properties

simple, low-memory algorithm; very efficient in practice

convergence in at most n n n

convergence rate depend on the distribution of eigenvalues of Q Q Q Q Q Q

in Python, implemented in scipy.sparse.linalg.cg

Nocedal, J., & Wright, S. J. (2006). Numerical optimization (Second Edition). Springer.